Published in BioLab Business magazine, Spring 2024

The Burrows Lab: disarming bacterial antimicrobial resistance

Work done at McMaster University laboratory aims to combat antimicrobial resistance in bacteria

With respect to some of the every day dangers that pose the greatest threat to the health and wellbeing of swathes of Canada’s population, few can match the destructive nature and capabilities of widespread harm than that of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria. Without the ability to effectively attack a viral bacterium with antibiotics and other medicines, illnesses and disease can escalate both in terms of the number of people impacted, and the severity of the impacts. With this challenge in mind, Dr. Lori Burrows leads the Burrows Lab, dedicated to working on enabling a deeper understanding of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria, and ways in which to disarm them completely, preventing their harmful effect on their victims.

“The Burrows Lab works on antimicrobial resistance in bacteria with a specified interest in biofilms, which are bacteria growing on surfaces, including medical devices, catheters, contact lenses, and so on,” she explains. “And, our ultimate goal is to figure out how to treat multi drug resistant infections.”

Leading lab

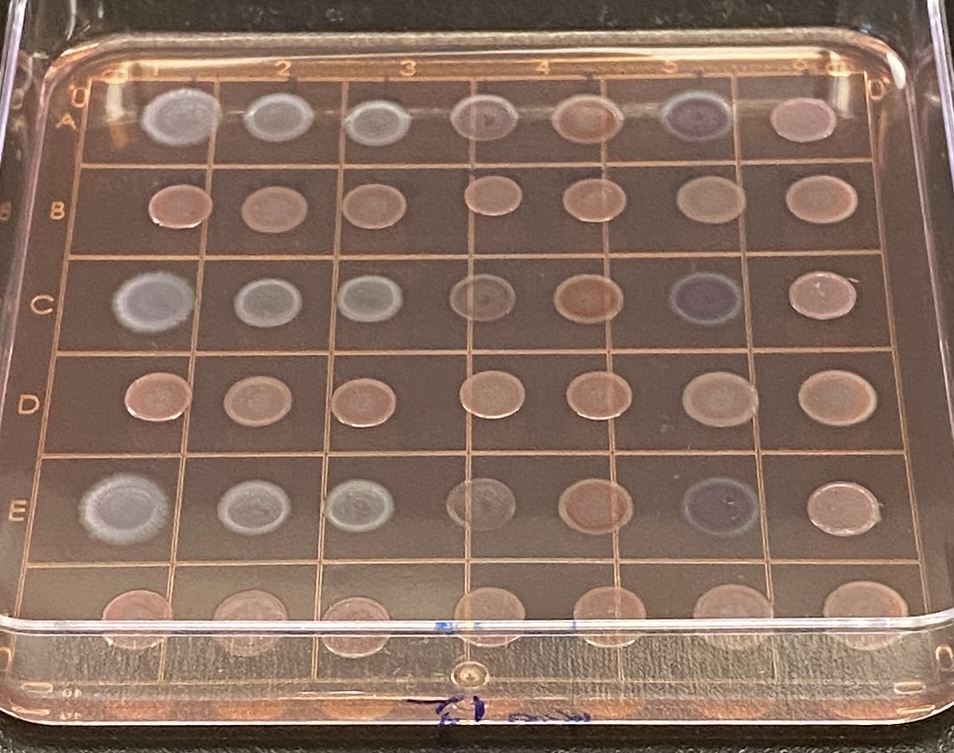

The Burrows Lab, which is part of the Michael G. DeGroote Institute for Infectious Disease Research at McMaster University, enjoys access to the university’s Centre for Microbial Chemical Biology, which is a high-throughput screening lab that can be used for the testing of all kinds of different drugs and compounds. The facility utilizes a robotic storage unit housing more than a half billion compounds, each of which can be retrieved for users by robots seamlessly. Operating the lab since 2007, Burrows’ focus has remained on the research that she considers critical to human health.

“It’s really important for scientists and researchers across the country and around the world to continue researching antimicrobial resistance, especially today given all of the pharmaceutical companies that have recently backed out of the space as a result of low return on investment for developing antibiotics,” she says. “Their departure has essentially left smaller biotech firms and academia to conduct drug discovery in the space. It’s a scary challenge given the fact that many of the antibiotics that we have are no longer working as well as they used to because of resistance.”

The importance of antibiotics

The seasoned microbiologist by training goes on to explain that, aside from the need for proper funding to fuel the required research, the critical need for effective antibiotics should in itself be enough to facilitate and elicit investor interest to help support the work done by Burrows and her team, and the work done at similar labs all across the country.

“If you think about it, what antibiotics do for us is essentially underpin all of the other fancy medicine that we develop and use,” she asserts. “We couldn’t do organ transplants without antibiotics because you have to immunocompromise people in order for them to accept the organs. We couldn’t treat cancer patients because we give them chemotherapy that causes immune compromising, making them extremely vulnerable to infections. We couldn’t keep premature babies alive. We couldn’t do hip replacements, knee replacements, all the stuff that we just take for granted as modern medicine. All of it relies heavily on the use of effective antibiotics. Even dentistry, for example, relies on the use of antibiotics. So, if the antibiotics don’t work, the rug is pulled out from underneath a whole bunch of other procedures that we expect.”

Phage therapy

As part of its ongoing research, Burrows and her team have started to pay particular attention to the study of phages and the ways in which they can be used as tools to combat certain types of bacteria.

“We use phages to probe different aspects of bacterial physiology,” she explains. “But we also realized that in the course of isolating these phages that they’re really good at killing dangerous bacteria. They don’t actually care if the bacteria is resistant to antibiotics because that’s not how their mechanism of killing works. They just basically invade the bacteria, and then turn it into a phage factory before it blows up and makes new phages. What we’re really trying to figure out, though, is whether or not we can use a phage against pseudomonas to kill it. It’s an organism that’s very challenging to kill with drugs. If you were to use these phages in the patient, what would be the most likely route that Pseudomonas would use to escape from the phages? Just like antibiotics, the bacteria can become resistant to phages, and we’re trying to understand how that could happen in order to inform methods of phage steering, which could ultimately lead to improved efficacy of treatments.”

Incredible promise

The Burrows Lab has actually been working with St. Josephs Hospital in Toronto to offer its phage therapy for patients with chronic urinary tract infections. And the Lab’s leader says that results have been incredibly positive.

“Some of the patients that have received the phage therapy have been on antibiotics for ages,” she explains. “One patient who was treated for an infection that lasted years, and who had already lost a kidney to the disease, was obviously quite desperate to receive some help for her condition. After some phage therapy treatments, her issues have resolved. It’s really exciting to be able to use this type of therapy, which is a kind of new old therapy. It was discovered more than 100 years ago, but it sort of fell by the wayside because antibiotics were developed. They present a range of great opportunities to enhance patient care through an advanced type of personalized medicine.”

Thinning brain-base

It’s incredible work that seems to be a great example of the ingenuity and innovation happening all across Canada’s life sciences sector. However, as Burrows points out, it’s ingenuity and innovation that is dependent on keeping our talented scientists and researchers here at home to further homegrown advances within the field.

“I’m an optimist by nature. However, the reality is that antibiotic resistance is increasing around the world. And, unfortunately, because so many companies have left the space as a result of economic perspectives, what we’re finding is that scientists and researchers who are doing work on antibiotics are leaving, too, for work in other therapeutic areas because it’s much easier to find a job working for a company that’s developing a cancer drug or some other type of therapeutic medication. As a result, we’re losing our brain-base within the field. And this presents a big problem because if we do eventually run out of effective antibiotics, without the prior study and research, who’s going to be there to develop the next ones?”